The Isle

Author: John C Foster

Publication date: 4 December 2018

Publisher: Grey Matter Press

Reviewer: Justin Hickey

If you’re going to set a horror story in New England, you’d better include nasty weather, cursed land, and locals who are slightly off. John C. Foster, author of the “Libros de Inferno” series, stirs all three components into The Isle, his latest book about a forgotten community off the coast of Maine. Forgotten, that is, until a person of interest escapes to and then dies there.

Richard Slocum is a federal fugitive. However, as Kittery’s Chief Roland explains, “He’s not dead until a federal or state ME officially says he’s dead.” Since the Isle isn’t part of Maine, just a territory eighty-two miles off its coast, this means collecting the body. The Isle’s own constable, a “right sonofabitch,” is willing to bury Slocum or float him home in a bag. Roland would be delighted if US Marshal Virgil Bone went after the remains instead.

And so would readers. From the first paragraph, Foster’s deft setup is awash in bleak New England imagery. Bone sits in a hearse that he’s driven onto a pier. A storm approaches over a ruddy Atlantic, and he “touched the change in his pocket, thinking about coins for the ferryman.” Bone, despite his sobriety and return from psychiatric leave, still reels from the death of his wife, Julia. Suicidal bravery is what he’ll need to face about three-hundred blinkered inhabitants of the Isle.

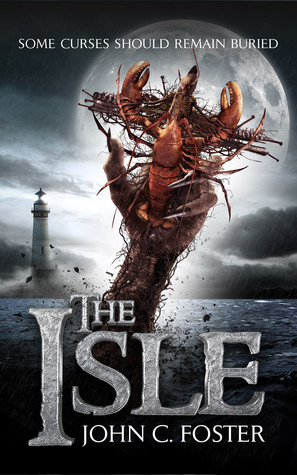

The book’s ghastly cover, featuring a not-quite-human hand gripping a lobster fetish, rings the dinner bell for horror fans. Yet even the most iconic horror emblems, like Pennywise the clown from IT, should only hint at the thematic depths explored by the narrative. Foster indeed takes us beyond the clawed-monster mayhem expected from his cover, into a deep history of evil, cultish behavior, and secrets worth killing for.

Suspense builds as Bone travels to the Isle on Samuel Weeks’ fishing trawler, the Leviathan. Weeks is a cagey weirdo who likes to poison gulls and turn them into chum. He also isn’t too thrilled by Bone’s presence: “Mainlanders are like bugs that leave tracks, if one comes out, more follow.” Before reaching their destination, Weeks drops anchor in the middle of the night to avoid jagged rocks (a different kind of Jenny Green Teeth than the English river crone), and tells Bone a story about his father and a black lobster claw almost two feet long. These eerie moments They likewise speed us through the story’s first third, giving the impression that Foster will guide his audience with a tight rein.

On the Isle, Foster introduces the rest of the cast, including dwarf Burden Ipswich, Increase Mather, and widow Hazel Milk (names reaching up from the dank, Puritanical past). And like birds of paradise, each character’s color seems magnified by isolation. Burden lives alone in a lighthouse, choosing the lofty company of two ravens, Huginn and Muninn. The constable is a super-creep who walks around with heavy pine for Hazel, who’s emotionally vulnerable. When she’s not home, he even rummages her bedroom and bathes in her tub. Their dynamic adds further heroic dimension to Bone’s arrival, yet the constable isn’t The Isle’s villain, despite Foster pitching him as such so well.

Perhaps most Gothically, a “psychotic but not dangerous” man named Enoch lives in the woods with his mother, Annie. Their home survives the warp and weft of New England lore, and “has the appearance of the forest’s secret expression, an enormous disembodied grin.” This pair drifts in the overlap between Foster’s brilliance for atmosphere and his kitchen sink approach to characterization. By the latter, I mean that not only is Bone a widower, but that his wife was pregnant—and cheating on him—when she died. He all but begs us to root for him. Yet he, and the entire cast, end up swamped by frothy exposition and coy plotting. It’s hard to tell what’s more important: the latest murder or a “puss-like eruption of crabs” assaulting Bone.

This may suit Foster just fine. Burden likens his own backstory to a “Robert E. Howard novel printed on cheap pulp with a lurid cover,” which we’d be crazy to take too seriously.

An abrupt, chaotic finale signifies that a ride has stopped, rather than that a story has concluded. Better still, that the weather has changed, and New Englanders know that feeling well.