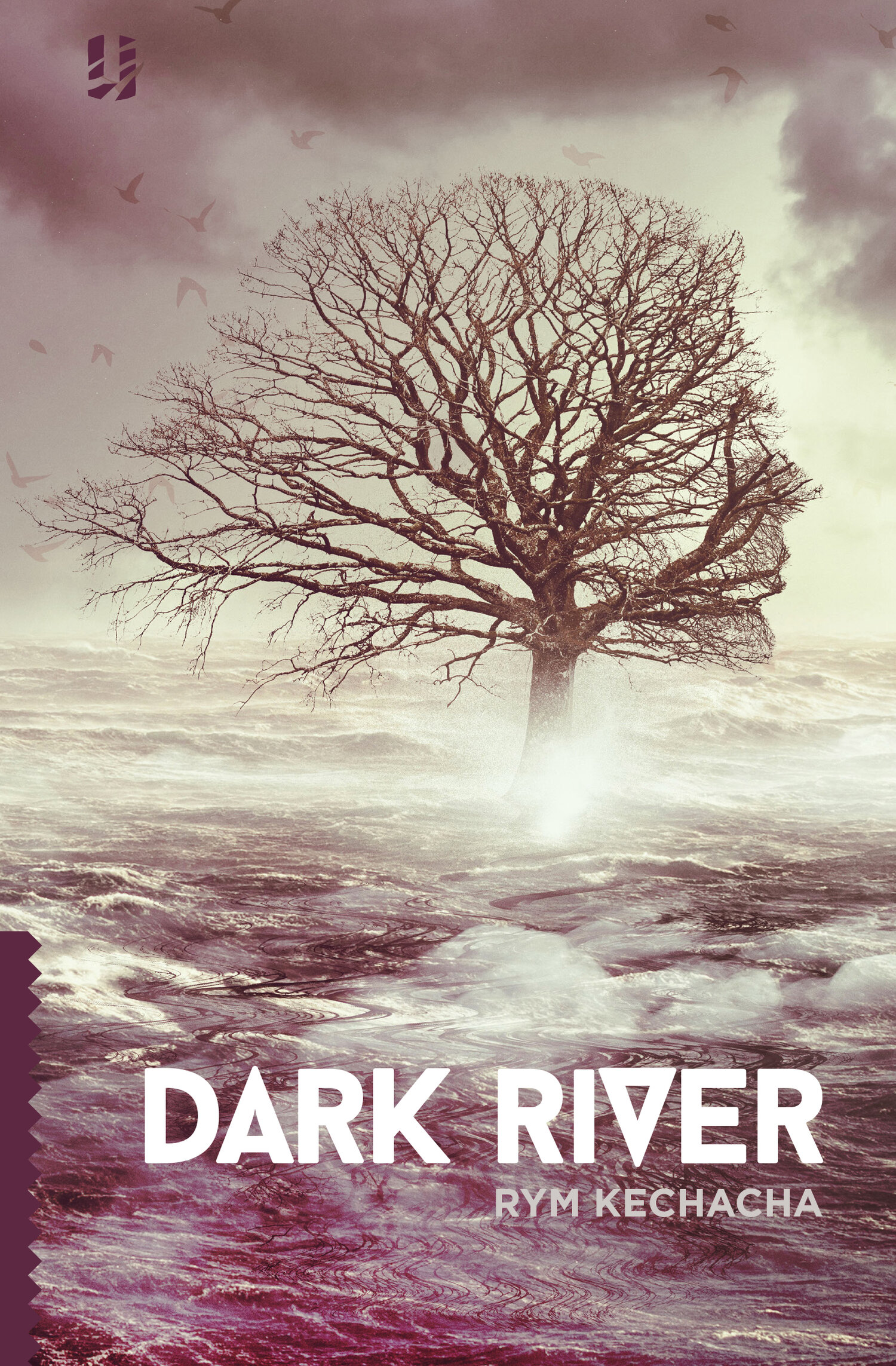

Dark River

Author: Rym Kechacha

Publication date: 24 February 2020

Publisher: Unsung Stories

Reviewer: Justin Hickey

The COVID-19 pandemic has curtailed humanity’s sprawl in the Spring of 2020. Quarantine guidelines instituted by governments across the globe have kept roads and waterways emptier than they’ve been in over a century. As a result, the skies over Delhi, India are experiencing record-low levels of smog. The canals in Venice, Italy, flow with transparent water.

Most scientific literature agrees that reducing fossil fuel dependence is the key to balanced, healthy ecosystems, if not for ourselves than for the millions of other species on Earth. Author Rym Kechacha, in her debut novel Dark River, focuses on the intimate human components of the Global Warming equation and questions how much we actually affect the planet’s geological movements.

The novel is split into two timelines with distinct casts. The first is 6200 BC, Doggerland, which was the land between Britain and Europe that the North Sea gradually swallowed. Here Shaye and her young son, Ludi, belong to a Mesolithic tribe that travels annually to a nearby oak grove to dance and “give thanks for the springtime and the rains,” and to, “ask for the land to come back to life again.” The river that sustains them throughout the year, however, is sick. The banks have flooded and it flows backward. It smells salty, “like promise, like moving on, like things growing elsewhere.”

A tribal elder, Old Cherl, says the river’s swelling is normal. “It’s what the spirits say is right.” More foreboding is that the tribe’s hunters never returned from their most recent hunt. Shaye struggles with visions of Marl, Ludi’s father, bedded down in another camp, with another woman. Yet leaving for the oak grove early, without the hunters, would be disastrous. Then a stranger visits. He tells the tribe that its hunters had to extend their journey to find enough game, and are already at the oak grove. On this stranger’s word, should the tribe depart?

At an invisible chapter break, Kechacha hurls readers into London, the year 2156. “It is a day when the river smells like petrol,” the narrator says of the Thames. This is Shante, a lute player with a young son named Locke. They live in Flood Zone One, an area subject to dangerous and erratic changes in the water level. While the prose depicting the past emphasises the naked grace and power of nature, here Kechacha is more fanciful. “The city has emptied like an upturned sack of spuds, its citizens rolling away in all directions, leaving mainly the poor, the stubborn and the careless behind.” Shante’s husband, Zeb, has already gone north with his passport. Shante waits for travel visas to come through for her son, father, and sister, Grainne, so they can follow.

Kechacha paints her two heroines, both embarking on perilous quests for the sake of family, as mirror images separated by thousands of years. Both narratives are studded with micro-dramas involving how much to carry, pregnant sisters, and the sacrifices of the older generation for the younger. Neither journey is sensationalised or rendered terribly cinematic. Staid travel exposition is only broken when sparks fly between people. For example, when Shaye finally reunites with Marl:

The sound of her name in his mouth makes her shiver, but she cannot say his. Her tongue lies thick on her teeth, and her belly is swooping. She forgets her hunger for a moment. She wants to answer him, she wants to say his name too. She wants to throw her arms around him and press her lip to that hollow on his neck where his jaw reaches his earlobe. She would have, once upon a time. She wonders why she doesn’t now.

In Dark River’s final third, the unique tragedies that strike each heroine give the narrative a much needed jostling. They are human-scale events, involving disease and death-lotteries, that play out intensely against the backdrop of a planet that, supposedly, doesn’t notice us. Shaye’s last chapter strengthens Kechacha’s core message that, “We are nothing at all to the earth, the sea or the sky, we do not matter.”

This nihilistic view is certainly supported by the geological upheavals that affected individual lives in the Mesolithic. The nightmares of 2156, however, are caused by humanity’s greed, prejudice, and arrogance. We may not matter to the earth, but to survive whatever the future brings, we must matter to each other.