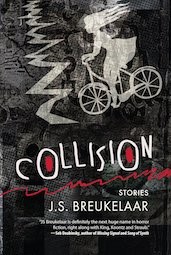

Collision

Author: J S Breukelaar

Publication Date: February 2019

Publisher: Meerkat Press

Reviewer: Kris Ashton

Speculative fiction is a broad marquee sheltering sci-fi, fantasy, horror, and almost innumerable sub-genres extending from those three main branches. One such sub-genre is “weird fiction,” and it serves as the connecting tissue for these short stories from J S Breukelaar. Weird fiction defies any firm definition or classification, except that it typically contains bizarre or surreal events applied to satirical or thematic effect. That’s certainly an apt description of Collision.

The weirdness in Breukelaar’s stories runs the gamut, from the simple but startling situation of a dog biting off a child’s hand, to entire tableaus given over to dark and disquieting fairy-tale imagery.

In “Union Falls,” the lead-off story and one of the strongest, a girl arrives at a bar and asks to audition as the keyboardist for the house band. Not so odd, you might say, except the girl, Ame, has no arms. As it turns out, she shows the other band members, particularly bar owner Deel, that they are the ones with no arms, metaphorically speaking, and helps them recover from their miserable situation.

The best stories in Collision follow this mould, drawing up a strange or uncanny scenario and then using it as a lever to deliver a message. In “The Box,” a man employs computer technology to create a virtual world where he and his dead wife can exist together once more. But the world is artificial and unwholesome and rather dishonest, more his idealised fantasy than a true representation of their life together. Below its sci-fi trappings, “The Box” is really about letting go of a deceased loved one and thereby freeing yourself, even though the act itself may be painful.

Where “Union Falls” and “The Box” are simple stories that examine the human condition, Breukelaar’s confessed love for Ray Bradbury (mentioned in the notes at the end of the collection) comes to the fore in the story “Raining Street.” What begins as an awkward suburban situation with an odd neighbour slowly spirals into a black pilgrimage of grief laced with allusions to classic fairy-tales, including “Hansel and Gretel” and “Jack and the Beanstalk” While it’s hard to know exactly what’s going on—the protagonist certainly doesn’t—this story typifies the author’s mastery of segueing from the everyday to the outright bizarre with such delicacy that the reader barely notices.

This approach works to even better effect in “Fairy Tale.” It is about a returned serviceman who thinks he sees the girl that shot him in the back while he was stationed in the Middle East and left him in a wheelchair. Except now she is dressed in cut-off shorts and high tops and rides a skateboard. He slowly befriends the girl—under the self-deception of “keeping his enemies closer”—and becomes a kind of mentor and guardian, taking her into his home and teaching her to play soccer. Once again, fairy-tale allusions play a big part in the story and it’s never certain whether the girl is real or part of a grand prescription-drug delusion.

Not every story succeeds, however, and those that don’t tend to be gratuitous; to indulge in weirdness for the sake of it. Take “Lion Man,” which begins with the aforementioned scenario of a dog biting off a child’s hand while her mother is on her mobile phone with her back turned. This startling image is the reader’s introduction to Turner and his dog Clint Eastwood, and a memorable introduction it is, but the story begins to lose focus after this auspicious start. I expected it to unfold into a biting satire, but instead it became just another weird tale (albeit one with some unforgettable imagery). It reminds me of Stephen King’s later work, where his apparently unquenchable desire to link everything to the Dark Tower universe has often led to weaker stories.

Then there are Breukelaar’s political allegories, which are rather too melodramatic for my taste. “Glow,” in particular, is about as subtle as a category five cyclone. But even these are tremendously effective in their use of language and style.

Misfires are few, though. In “Rouges Bay 3013,” combining human DNA and computer code leads to some unusual family dynamics and a different take on the afterlife; “War Wounds” is a curious but effective mash-up of a coming-of-age tale and a ghost story in a bucolic post-war setting; and I adore the sense of place Breukelaar creates in “Ava Rune” (which could well be retitled “Carrie in Rural Australia”).

Weird fiction can be confusing and tiresome if it doesn’t have a strong narrative drive, but Breukelaar’s delectable prose draws in the reader, and I frequently found myself in that perfect hypnotic state where I forgot I was reading—the highest honour one can bestow on an author, in my opinion.